Info

Official Name : Louisiana Museum of Modern Art

Address : Gl Strandvej 13, 3050 Humlebæk, Denmark

Type : museum

Year of Completion : 1958

Architects : Jørgen Bo, Vilhelm Wohlert

Opening Days :

Tuesday – Friday (Weekdays)

Saturday – Sunday (Weekends)

Closed every Monday (Please check for exceptions on public holiday Mondays)

Opening Hours :

Tue-Fri: 11:00 – 22:00 (Evening opening)

Sat-Sun: 11:00 – 18:00

Admission (2024–2025 Standard) :

Adult: 145 DKK (Approx. 29,000 KRW)

Student: 125 DKK (With valid ID)

Under 18: Free

Visitor Tips :

– Weather: As the museum interior and the outdoor sculpture park are connected, visiting on a clear day is recommended.

– Route: Whether you go left (Modern Art Collection) or right (Special Exhibitions) from the entrance, the layout is circular, bringing you back to the start.

– Dining: The “Louisiana Cafe” is famous for its breathtaking view of the sea (The Sound/Øresund). The Danish open-faced sandwiches (Smørrebrød) and the buffet are recommended.

Official Links

Introduction

[A Humble Alliance of Architecture, Nature, and Art]

About 35 minutes by train from Copenhagen, Denmark, if you walk along a forest path from Humlebæk Station, you will encounter a vine-covered building that looks like an ordinary family home. This is the Louisiana Museum of Modern Art, often accompanied by the epithet “the most beautiful museum in the world.” This place differs entirely from typical museums where colossal, monumental structures dominate the surroundings. The founder, Knud W. Jensen, dreamed of a space where “the guest, not the art, is the master,” and architects Jørgen Bo and Vilhelm Wohlert translated this philosophy into a perfect spatial language.

The core of the Louisiana Museum is “humility” and “connection.” The architecture never attempts to defy or overpower nature. Instead, walls were curved to avoid cutting down old trees, and floor levels were adjusted to follow the slopes of the terrain. By using the existing 19th-century villa as the entrance, it offers the comfort of being invited into someone’s home. From this point, the glass corridors extend outward, constantly guiding visitors into the world of art, the Danish forest, and the dazzling Øresund Strait.

The architecture here is not merely a background. Visitors view artworks, then gaze outside through floor-to-ceiling windows to rest their eyes before moving to the next gallery. The founder called this the “Sauna Principle.” He imbued the spatial experience with a rhythm similar to enjoying a hot sauna (focused art appreciation) followed by a dip in cold water (relaxation in nature).

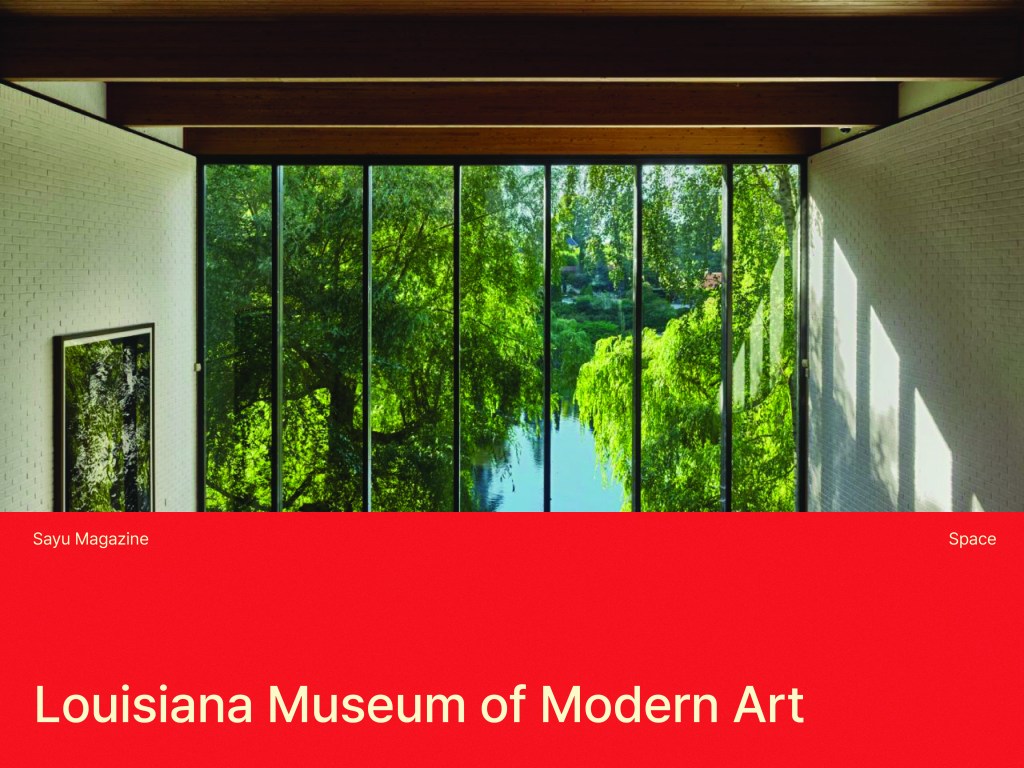

Whitewashed brick walls, red tile floors, and warm wooden ceilings showcase the essence of Danish Modernism. Instead of ornate decorations, light, shadow, and the changing seasons outside the windows fill the space. In particular, the ‘Giacometti Hall,’ where Alberto Giacometti’s sculptures stand, offers an unforgettable aesthetic experience where artificial lighting, natural daylight, and the lake outside the window blend to unite the artwork with the space. Louisiana is not just a building; it is a grand journey of encountering art as if taking a stroll through nature.

Architectural History

1958: Opening of the main building (existing villa) and the North Wing by founder Knud W. Jensen and the architects. The beginning of the pavilion structure connected by glass corridors.

1966: Extension of the West Wing.

1971: Extension of the Concert Hall. Expansion beyond a museum into a cultural complex for music and performance.

1976: Addition of cinema and theater facilities beneath the Concert Hall.

1982: Extension of the South Wing. Secured spaces with high vertical clearance for large-scale artworks.

1991: Completion of the Graphic Wing and underground spaces. Completion of the circular flow, allowing visitors to tour the entire museum without interruption.

1994~1998: Construction of the Children’s Wing and modernization renovations.

Present: Continuing to perform modern functions while maintaining the original form of 1958 through ongoing maintenance and minor renovations.

Architectural Features

(1) Horizontal Integration with Landscape

The most defining characteristic of the Louisiana Museum is that the building does not reign over the land but ‘permeates’ it. When architects Bo and Wohlert began their design, they identified the locations of trees, the elevation of the terrain, and the viewpoints of the sea before looking at architectural drawings. As a result, the building was designed to be thoroughly horizontal.

With the exception of the existing 19th-century villa, all buildings were designed as single-story or low-profile structures, to the point where they are often hidden by the forest when viewed from the outside. This is to avoid disrupting the flow of the terrain. “Skip floors,” where walls curve to avoid tree roots or floor levels adjust naturally with a few steps along the slope, appear frequently.

This horizontal layout provides psychological comfort to visitors. Instead of the authoritative attitude of imposing, large museums, it evokes the feeling of a shelter stumbled upon while walking in the woods. The building itself becomes a ‘frame,’ and the Danish old trees, bushes, and the horizon of the sea seen through the windows are completed as part of the architecture. In other words, the architecture here assumes the role of a vessel for nature, succeeding in erasing the boundary between the building and the landscape.

(2) The Glass Corridors & Blurring Boundaries

Connecting the various pavilions of Louisiana are long “Glass Corridors.” These corridors are not merely passageways. By finishing both sides, or one side, of these narrow, long hallways with floor-to-ceiling glass, they create the illusion that visitors are walking through the forest even though they are indoors.

Architecturally, this space serves as a “Transition Space.” After viewing intense artworks in one pavilion, visitors receive natural light and watch the leaves rustle while passing through this glass corridor to the next pavilion, washing away visual fatigue. This maximizes the characteristic of Modernist architecture that breaks down the boundaries between the interior and exterior.

The glass frames use thin wood or dark metal to minimize visual obstruction. The red tile floors start indoors and extend beyond the windows to the outdoor terrace, creating a visual effect where the interior space expands outward. Depending on the season, weather, and time of day, the light and shadow cast on the glass corridors create a different spatial sense every time, giving the impression that the building is alive.

(3) Vernacular Modernism & Materiality

The Louisiana Museum is not a high-tech building constructed solely of cold steel and glass. Rather, it implemented “Vernacular Modernism” using warm, simple materials found in traditional Danish homes.

The primary materials are Whitewashed Brick, Red Quarry Tiles, and Laminated Wood.

- Whitewashed Brick Walls: White paint applied over textured bricks creates a neutral background that does not interfere with hanging artworks, while still providing depth to avoid blandness.

- Red Tile Floors: The rough-textured red tiles create a warm, domestic atmosphere. This is a key element that makes visitors feel comfortable, as if they are in someone’s living room rather than a public institution.

- Wooden Ceilings: Exposed wooden beams and panels on the ceiling add rhythm, soften the acoustics of the space, and add visual warmth.

These materials have the characteristic of gaining a “patina” rather than looking worn out over time. The reason the sections built in 1958 and those built in the 1980s blend without disparity is due to the consistency of these materials and the durability provided by their physical properties.

(4) The Sauna Principle & Circular Flow

The “Sauna Principle,” advocated by founder Knud W. Jensen, is the core philosophy of Louisiana’s spatial layout and circulation planning. Just as Danes enjoy alternating between the intense heat of a sauna (focus) and cold water (relaxation), museum viewing should also be a repetition of “Concentration” and “Relaxation.”

Architecturally, this was implemented by alternating exhibition spaces (closed spaces, artificial lighting, focus on art) with rest spaces (open spaces, natural light, view of the landscape). After viewing a dense exhibition, visitors inevitably take a breather through a glass corridor, a cafe, or a door leading to the garden.

Initially a “U”-shaped structure, the museum completed a massive “O”-shaped (or distorted circle) circulation path with the completion of the Graphic Wing in 1991. This ensures that visitors do not have to turn back at a dead end but can naturally tour the entire facility like flowing water and return to the entrance. In this cycle, visitors experience various sequences: descending underground, seeing the forest, and facing the sea. This circulation design is an architectural device that eliminates boredom and encourages visitors to stay for a long time.

(5) Light Modulation & The Giacometti Hall

The architectural highlight of the Louisiana Museum lies in “the way it handles light.” In particular, the “Giacometti Hall” located in the North Wing is a textbook space showing how architecture, art, and natural light harmonize.

This space was designed for Alberto Giacometti’s thin, elongated sculptures. It features a double-height ceiling to emphasize the verticality of the statues. The most significant feature is the full floor-to-ceiling window and skylight. One entire wall is made of glass, making the lake and willow trees outside the direct background of the space.

Natural light, changing with the seasons and time, breathes life into the sculptures. The subdued light of a cloudy day maximizes the solitude of Giacometti’s works, while the sunshine of a clear day highlights the texture of the pieces. The architects designed artificial lighting to be supplementary, allowing natural light to be the protagonist illuminating the works. This perfectly demonstrates the architect’s intention that “artworks should not be trapped in a sealed box but should breathe with the world.”

Source Caption

This text was written based on the official website of the Louisiana Museum of Modern Art (louisiana.dk) and architecture-related resources. Operating information may vary depending on the time of your visit, so please check official channels.

댓글 남기기